Opinion: Game company acquisitions & the 'growth stock bubble'

Publikováno: 18.12.2020

Gonna roll 'em all up.

[The GameDiscoverCo game discovery newsletter is written by ‘how people find your game’ expert & GameDiscoverCo founder Simon Carless, and is a regular look at how people discover and buy video games in the 2020s.]

For the final GameDiscoverCo free newsletter of this week, we wanted to bust out a spicy opinion piece that’s perhaps not as granular as ‘what new feature did Steam launch?’ But it’s just as relevant for the future of how games are bought, discovered, and played.

Why are some companies in the game biz - from Embracer Group to Keywords to EG7 & beyond - going on studio buying sprees right now? (I did make a joke after Embracer bought 12 game studios & a PR firm recently: ‘Scoop: Embracer Group planning to change its name to Katamari Entertainment.’)

Should we be worried about it, why is it happening, and what are the larger financial underpinnings? Since I’m under the impression I know ‘enough to be dangerous’, I’ll have a crack at this topic, albeit from a slightly grumpy perspective.

Why so many game studio acquisitions?

Let me start with a thesis. The pace of game development (and outsourcing studio, and publisher, and other entity) acquisitions is reaching a fevered pace in certain areas that sometimes makes onlookers say ‘???’

And there’s one reason for that. The public financial markets are completely fine with massive, (initially) unprofitable* consolidation of game companies. (*Unprofitable including acquisition costs.) This is largely because revenue growth, not profit, drives company stock price in the global markets right now.

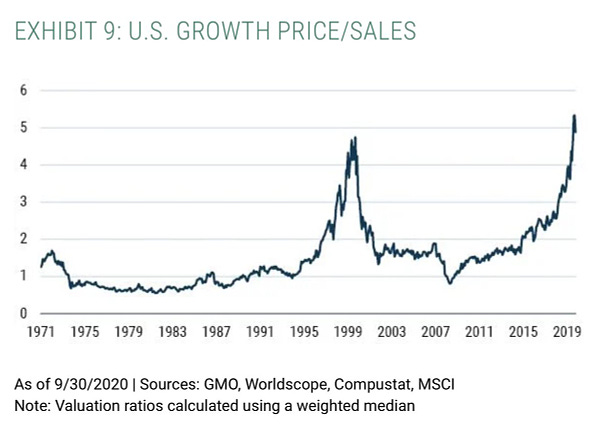

This is something that hasn’t been so much the case since, uh, just before the 1999 crash. Look at this:

This is just for U.S. stocks, but the message is obvious. ‘Boring’ companies that are conventionally profitable are out. ‘Sexy’ companies that are growing revenue massively, but losing scads of money - or, sure, barely breaking even - are in.

Here’s a valuation-related example in the game space: although kids online behemoth Roblox just delayed its initial public stock offering (IPO) because it’s concerned about valuations, its S1 filing before its stock debut revealed that it lost $48 million in the last quarter on revenues of $242 million, but with revenue up 91%. And let me just clip this paragraph from the CNBC Roblox story for you so you can goggle:

“Unity just reported third-quarter revenue growth of 53% to $200.8 million and it’s valued at $32 billion. Roblox is bigger and growing faster. Based just on a comparable multiple to annualized revenue, Roblox would be worth over $37 billion.”

So.. there’s some math, wow. You can be losing $500,000 per day and be valued at $37 billion. This is not conventional company valuation etiquette. (If you go back far enough and look at conventional businesses, a company would be bought or valued at a multiple of its yearly profit, sometimes 8x to 12x profit. But many tech companies are valued at high multiples of revenue, not profit.)

Of course, when companies go public, all shareholders - including company founders and veterans - get a slice of that massive (in my view, fairly illogical, but that’s where we are!) valuation. And then they can sell their shares to investors, sometimes after a lock-up period.

There’s a lot of money to be made here - much more than ‘profit on making a game’, unfortunately. So… if you’d like to go public as a game company, or already did so, and you’re not growing swiftly enough, what can you do to increase your growth velocity and therefore valuation? Perhaps you could… buy a whole bunch of other game devs or publishers!

The four tiers of game company rollup structure

Now, I hasten to add that I don’t think what any game companies buying other companies are doing is ‘fundamentally wrong’, per se. Especially not if you actually can get ‘synergies’ through purchases - hopefully not just cost savings, but also ways to make your customers happier - and make your business run better.

There are just varying levels of transparency around the actual profitability of the parent company, and varying possibilities for the end game in a few years... and I really think it’s worth looking into those. So here we go:

1. Conventional private companies

Some of the acquisitions we’re seeing are just from private companies who are doing well - Devolver buying long-time partner & Serious Sam dev Croteam being one of them.

I don’t think Devolver is issuing shares or has talked about valuations internally (though I could be very wrong!) I think it just has a lot of leftover money because of Fall Guys’ massive success, so decided to pay out and buy a partner.

So that’s one cleaner type of consolidation that I see. ‘Excess company profit, let’s buy another company to partner with them better long-term and reward them’. (Another debt-based version of this would be ‘we borrow money from a single investor or a bank to make acquisitions’. Debt is very cheap right now and can be paid back gradually, like a mortgage. All fairly conventional stuff.)

2. Private equity

So, private equity are investment funds that generally - historically - have bought and restructured troubled companies to maximize profits, and then either re-sold them or took them public. (Private equity has sometimes had a bad reputation for ‘asset-stripping’, and they’ve been ruthless at times on costs.)

Private equity is definitely more interested in video games than it used to be, in part because of the public performance of ‘growth stocks’. (If you can take a company public without it needing to be super profitable but still get an excellent valuation, why asset strip it?)

A good example of this in the video game space is Curve Digital (Human Fall Flat), which was acquired by by NorthEdge Capital in a deal worth £90 million in late 2019, and has been making multiple acquisitions recently, including For The King dev IronOak Games and, semi-indirectly, Bomber Crew developer Runner Deck.)

Curve is now discussing going public, an obvious private equity end-game - though I’m sure it wouldn’t mind being acquired before then, if it’s a better end result.

And I will note that Curve, like a lot of the UK companies we’re about to discuss, is growing and profitable, at least according to its official comments. They may be borrowing money to do limited acquisitions in hopes of a good ROI down the road, but it’s a milder version of things we’ll see later. And it makes sense to pick up valued dev partners and bring them in-house & pick up all the royalties on subsequent games.

Given that high-profile public UK game companies like Codemasters, which has done a good job of pushing profits recently after many workmanlike years, can get acquired by Electronic Arts for $1.2 billion (at more than 30x profit!), you can see why the hotness of the market is tempting right now. Small profits can still mean high valuations.

3. Public companies in the U.S. or U.K.

So, let’s go to ‘conventional U.K. and U.S. companies’. The big folks like Electronic Arts (U.S. traded) are seeing soaring valuations because of COVID lockdown, the success of their games, and the general frothiness of the markets.

But these companies still make money and generate cash, even if they sometimes have corporate debt lurking in the background somewhere. And the U.S. and U.K. stock exchanges force public companies to be fairly transparent about how much money they’re actually making every quarter.

So, for smaller U.K./U.S. companies wanting to grow quicker or make its owners cash, obviously there’s the big payout when you go public (your shares are suddenly worth a lot of real money!) But what’s an amazing alternative to borrowing lots of money, if you are public? You can issue new shares, and sell those to generate money to do new things like buy new companies.

If you look at Team17’s public offering in 2018, for example, it was “based on the issue of 27,325,482 new shares and 37,849,200 existing shares, at a price of £1.65 per share.” So, tens of millions created by selling new shares to new investors. Who are happy, since T17’s share price has quadrupled since then, btw.

Due to Team17’s increasing revenues and actual profits (profit before tax of UKP 13 million), and plenty of cash on hand presumably due to ‘real’ profits and new share issuances, they have lots of money to play with. (Although, with a couple of exceptions, Team 17 is not going on a buying spree.)

One more aggressive public acquisition example here: Keywords Studios, which is publicly traded in the UK and has been rolling up tens of video game localization, testing and outsourcing companies, just picked up High Voltage Software for $50 million.

This seems a little frothy to me for a veteran dev turned high-end outsourcing studio, though it includes incentives which may not be met and a high possible 2021 earnings target for High Voltage.

Anyhow, Keywords recently raised 100 million UKP in a share placement, which really cost them nothing to do. And provides the next roll-up funding tranche. Keywords does, however, at least have a good theoretical acquisition synergy pitch - they can be a ‘one-stop shop’ for everything to do with game services, and their companies can work slickly together.

The point here is - higher stock prices mean higher overall company valuations, even on transparent stock exchanges like the U.S. and the U.K. Which means it’s easy to either borrow a lot of money or issue new shares to create more money to, uh, grow faster and buy more things. Do you see where the financial markets may be encouraging consolidation and ‘winner takes all’ trends?

(Related: I didn’t talk about Xbox’s massive dev studio spending spree yet! They have a U.S. tech giant ‘daddy/mommy’ in Microsoft with over $130 billion cash on hand, and generating even more profit every quarter. So as long as these studio pickups help plan Game Pass’ rise to subscription glory, it’s all good.)

4. Public companies in markets like Sweden

And here’s where we get to the most aggressive Katamari crew of all - the publicly-traded Swedish companies. There are a number of them, including and not limited to Embracer Group, MTG, Stillfront, and EG7.

And what’s really interesting about them is that they’re not really pushing a traditional ‘synergy case’ for combining game companies as much as just saying ‘no, we’re going to buy a bunch of stuff’. (EG7’s latest financial report has far more references to M&A than synergy, for example.)

As to why they are so aggressive, I was amused to see this brochure for the NASDAQ First North stock exchange say: “In Sweden, there is a long tradition of self-regulation in the securities market, which serves as an alternative or complement to legislation.”

So, a fairly relaxed market, in other words - and certainly fine with companies issuing lots of stock and taking on debt to keep buying and expanding, rather than being very profitable with long-established products and returning dividends to shareholders. (Mind you, most of the world seems to be like that. I’m just noting that these companies seem to be on the bleeding edge of this trend.)

And the way earnings need to be stated in Sweden aren’t quite as direct as the major markets. For example, I tried reading Embracer’s financials, as a former EIC of Gamasutra who regularly wrote up quarterly earnings from big U.S. and U.K. game companies, and they are not that easy to grok/understand for me past the top-line numbers.

The up-front revenue and profit from acquired companies is clear. But under the hood, there’s some extremely complex amortization of game projects and even some IP valuation and amortization. But overall, it seems like ‘paying companies with our shares and issuing new shares’ - with some debt borrowing - is the chief funder of big new acquisitions at Embracer and likely all of these Swedish public game companies. (It’s like a non-stop fountain! Because the valuations are so bullish, issuing new shares is ‘free’ if you do it gradually…)

Moving elsewhere, let’s focus on EnadGlobal7 (EG7) for a second, maybe the most aggressive of the lot. EG7 bought Everquest publisher Daybreak for $300 million the other week, including lots of stock, and Mechwarrior dev Piranha Games for anywhere between $25 million and $70 million depending on long-term incentives just before that.

I’m not really qualified to talk about the absolute details of those particular deals. But I notice that the Deconstructor Of Fun crew did so on a recent podcast transcription, and those folks are whizzes at this type of thing.

Adam Telfer commented that what used to happen, acquisition-wise was “…capturing a bunch of lower tier devs at a discount and helping them grow if you can acquire them cost effectively. But that’s not what’s happening in 2020… lower tier studios are getting snapped up at frothy multiples based on inflated rev… this isn’t bargain shopping.”

And here’s Joakim Achren, in particular re: the Daybreak acquisition, which has a lot of older MMOs in it: “You've got a handful of Swedish public companies that specialize in consolidation. You've got opportunistic gaming studio owners.. Match these two and in the short term, things will look glamorous… In a few years, these studios [like Daybreak] need to start making new titles… the jury is still out [whether] any acquired studios create value from new games.”

So, the theme is willingness to back ‘growth stocks’ from companies whose massive ‘rollup’ sprees are funded by new share issuances or corporate debt - even minus any substantial synergy cases. And it reaches its peak in the Swedish market with some of these recent deals.

I admit this opinion piece is colored by my annoyance over the state of inequality and capitalism - and my simultaneous knowledge about how it works, oh no. But as for what’s happening in the long-term with this style of roll-up company model, I’ve got no idea. Embracer raised another $161 million for acquisitions earlier this year without any problem. And the share dilutions aren’t affecting share prices right now. Plus - the companies being bought are mainly - in themselves - profitable.

So, yep - I can’t see a hole in this model until the stock market no longer (over?) values growth stocks, or if one of the companies gets overaggressive and loses investor confidence somehow (see: Starbreeze). So I guess this consolidation boom is just going to ride until it can’t ride no more…

[Thanks for reading this! Feedback, corrections and opinions welcome. As always, we’re GameDiscoverCo, a new agency based around one simple issue: how do players find, buy and enjoy your premium PC or console game. You can now subscribe to GameDiscoverCo Plus to get access to exclusive newsletters, interactive daily rankings of every unreleased Steam game, and lots more besides!]